Scores and Maps

A score is not music.

A score is a silent document made of paper and ink or of pixels on a screen.

A score is, though, as Philip Thomas describes it, a ‘prescription for action’. That is, it’s a script or a recipe that enables things to happen in a particular way that, when we add the graft or labour of our action, gives rise to music. And it’s that ‘particular way’ that encodes the characteristics of the music; its essence or identity; its specific nature, in sound, that renders it recognisable and repeatable (though hopefully not too much so).

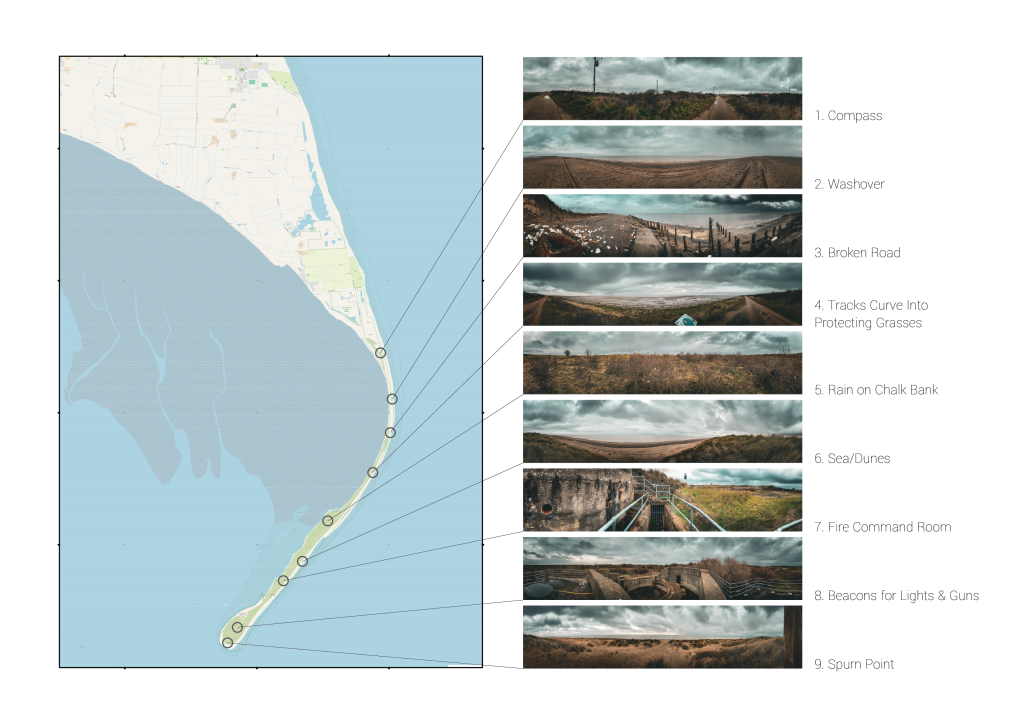

Creating the score for Coastal Process is about encoding the permissiveness of the improvised approach that is at the heart of all of my composition and production as seen through the lens of the landscape of Spurn Point. Freedom is an essential ingredient, but it is not about the pursuit of total freedom. What is total freedom, anyway, except for an abandonment of specificity?

Instead, the piece is about exploring a metaphorical relationship between the spontaneous act of traversing a landscape on foot and the improvised responses we can give in performance. Our map in hand, we have a general sense of where we are now and where we’d like to be in the future. But the step-by step-progress is inflected by what we encounter along the way, which nudges us this way and that. Similarly, our score in front of us plots a route but only comes to life by the moment-to-moment decisions we make in chaining together sounds, one inflecting the next and the next and the next.

Scores and maps are kin.

Download the score and Ableton Live set for Coastal Process here

Freedom & Improvisation

Freedom in an improvisatory context is about moving about a frame; it is about moving freely within a frame just as freedom to explore a landscape is bounded by our very human physical capacities.

Notating freedom draws out the contradictions of the very liveness of music (that it is a shared, unrepeatable experience) and the fixity of score as object. We need to fix an object to communicate our ideas at a distance, akin to Bruno Latour’s idea of ‘immutable mobiles’ that fix and preserve ideas that can be moved, shared, dispersed. But we need to fix the permission for freedom.

In notation, this seems to lead to a significant increase in the number of words needed in an inversely proportional relationship to the amount of graphical (perhaps staff-based) notation that is created. What is gained for the sense of freedom on the part of the performer by shedding some of the restricting elements of traditional notation comes at the cost of having to verbalise, to permit in words. But that, for me, is a price worth paying.

So, the challenge of creating this score has primarily been about what words need to be included so as to explain the origins of the thinking that gave rise to the piece as well as the practical approach that a performer might take. It’s been about finding the sweet spot between constructing the frame and leaving as much room for exploring as possible.

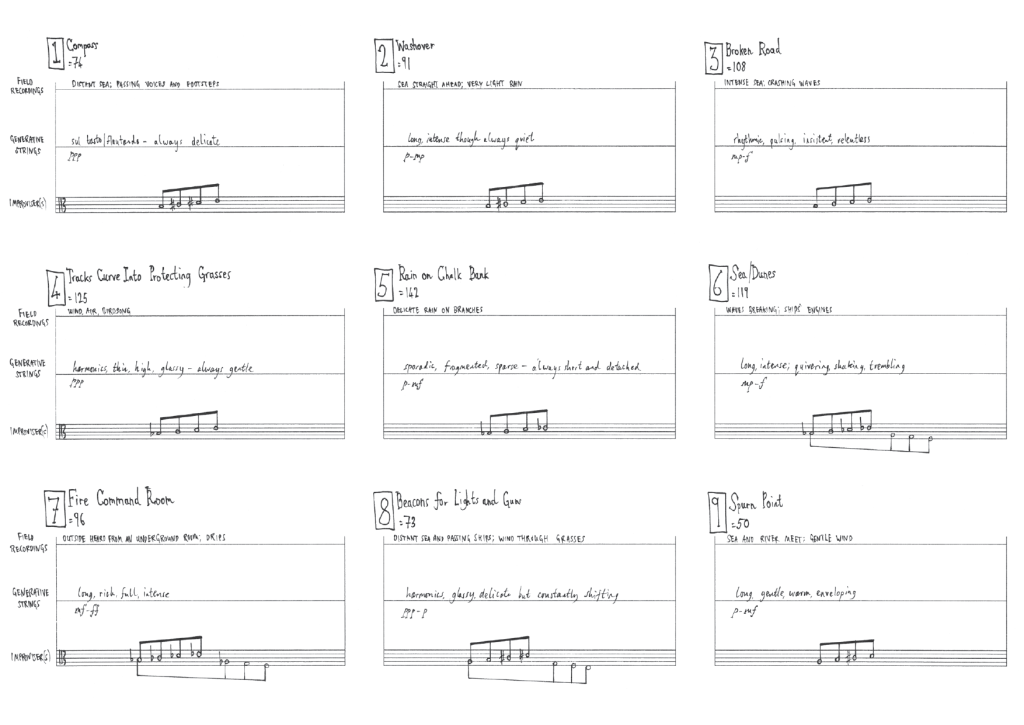

Elements of the Score

The pages of the score are mostly text. It opens with an explanation of the title – Coastal Process – and the physical processes at play in a coastal system are related to a compositional mode of activity. The next three sections explain: 1) the field recordings; 2) the generative string section; and 3) how the improvising performer(s) might approach the work. The Ableton Live session file is explain next with two possible approaches (a simple way of doing things or a more complex approach for those with more experience and confidence with the software and technology).

The final page is a one-page notation that encapsulates the whole 45-minute, nine-section span of the piece. It contains stave lines for the field recordings (with sparse descriptions offered that are derived from my understanding of the qualities of each piece of audio), the generative strings (with descriptions about articulation, timbre and techniques), and finally the part for the improvising musician(s).

This final element contains what might be normally thought of as notated music: pitches plotted on a staff. These pitches form tetrachords (basically, a four-note collection of pitches) which can be used (or added to or ignored) for the improvised response. These tetrachords undergo a very simple process of alteration across the span of the piece, which is metaphorically compared to the movement of a single pebble along the coast through the action of the tide.

These pitches are notated using the alto clef. This choice was made for two reasons. First, the clef (which denotes that the middle line of the five lines of the staff is a middle C) positions the tetrachords centrally within the staff. This removes the need for ledger lines for plotting pitches, which makes the notation more direct. Second, the alto clef is one of the rarer clefs (except perhaps for viola players and trombonists) so it goes some way towards removing and instrument-specific implication. For those less familiar with the clef, it might need just a little more consideration, which might throw attention onto the sounds being created as opposed to any harmonically driven logic.

The Difficulty of Fixity & Permission

All scores are graphic scores in that they encode ideas about the organisation of sound in some kind of visual form.

There are things, then, that are extremely hard to avoid due to the way someone will read the notation (e.g. from top to bottom, from left to right; though, of course, there are textual cultures whose direction of reading is different from that). The tetrachords are indicated starting at the lowest pitch with the three following notes presented in ascending order (in terms of frequency, or higher pitch). In this form, there’s an implication then of ordering – that the first pitch we see when reading from left to right is more important. Perhaps it should come first or be emphasised so as to establish a root note (which underpins all tonally-centred forms of music). Should any melodic elements proceed in a stepwise manner? And can pitch equivalents be used (e.g. at different octaves and in different registers)?

Another difficulty is that fixing things textually and graphically in this way can undermine the permission to add, amend, omit, ignore or deviate. It is a deeply embedded value in literary cultures that a written document has authority. And what was initially a desire for clarity might spill over into dogma. Here, I want performers to encounter the sounds on their own terms (though I have curated them) and to use this frame merely as a starting point. That permission is difficult to convey when it is offered in a form which carries with it such powerful associations with incontrovertible fixity.

Finally, I have made a recording of this piece. What effect might that have on future performances if performers choose to consult it? Does that also become a primary text, which undercuts the exploratory improvisation that is really driving the creative impulse of this piece? What might once be a form of versioning or illustration could have a concretising effect that works against the essence of traversing this landscape, maybe akin to a form of tourism where we have to follow those officially-sanctioned neat pathways instead of the impulse of our own curiosity.