Spurn Point transect walk done, wet clothes dried and feet warmed up, the next question is: how to use this sound-material as the basis for a composition? And this then prompts further questions about how to treat those sounds (which is partly an ethical issue), what do those sounds do in terms of prompting (or demanding) further responses, and what might be asked of musicians in the future who might engage with this piece. This post is, then, about compositional decision-making which is both technical (how to assemble and control sound materials) and aesthetic (what position to take in relation to styles and practices in music).

What is certain

I usually start by working out what I know for certain and then teasing out from that what my position is. That all points me along a certain path, which eventually becomes the piece of music (though I’m not really interested in the idea of ‘pieces’ as fixed, repeatable entities – more like sites that create opportunities for making music).

What I know for certain is that the piece will be called Coastal Process (a term which came up several times in the interviews throughout this project and was emphasised as being importantly different from ‘coastal erosion’). I also know that the work will have nine sections each of around 5 minutes in duration in a direct relationship with the field recording locations from the transect walk. And I also know that it’ll be for improvising musicians (or just one musician) featuring whatever instrument/voice/object is their thing.

From a compositional point of view, what do these things say? First, the close relationship that I want the musical work to have with the geographic contour of Spurn Point is about preservation and respect. Sound is removed from its original coordinates; its transience undercut by digital storage; its uniqueness diluted through repeatability. I want these sounds to invoke the sense of standing exactly where I stood to record, to give a sense of being there. This rendering as stable is necessary to make a piece like this, but it also does something odd to those sounds in that it severs the connection to place and moment. It’s a bit like taking a box of sand from a beach (which you shouldn’t do) as a way of remembering the beach. That box of sand immediately becomes something else, something out-of-place. The same with sound – the separation of sound from place is a necessary incision, but one that isn’t without a cost. Working with field recordings is at once potent reconnection to and loss of the sense of the place.

Second, the focus on improvisation is (in the most straightforward way) a reflection of my long-standing interest in this mode of music-making. So, that’s not surprising or new here. But beyond that, improvisation has, for me, a metaphorical power connected to what we do when we explore a place. Turn up on the outskirts of a forest that you haven’t visited before and you find your way step by step, making decisions about which fork to take in the path, which hill to climb, where to stop and stare. This was the sense I had when traversing Spurn Point (pick a spot that catches my eye, follow the undulation), so this is the sense I want musicians to have in navigating the prised-away sonic version of this landscape. The plotting of every note on a score, for me, has an absurdity akin to precisely plotting someone’s every step along a sandy peninsula.

So, the piece plots a course from what is certain to what is not (and embraces that uncertainty by inviting musicians to respond).

Organising sounds

John Cage and Igor Stravinsky, though different in many ways, shared a common view about the power of observation – of being able (and willing) to see what is around you, something just waiting to prompt a response if only we accept it as a possibility. Spurn’s sound, its geographic behaviour, and my sense of being there are the elements from which I draw patterns to underpin Coastal Process.

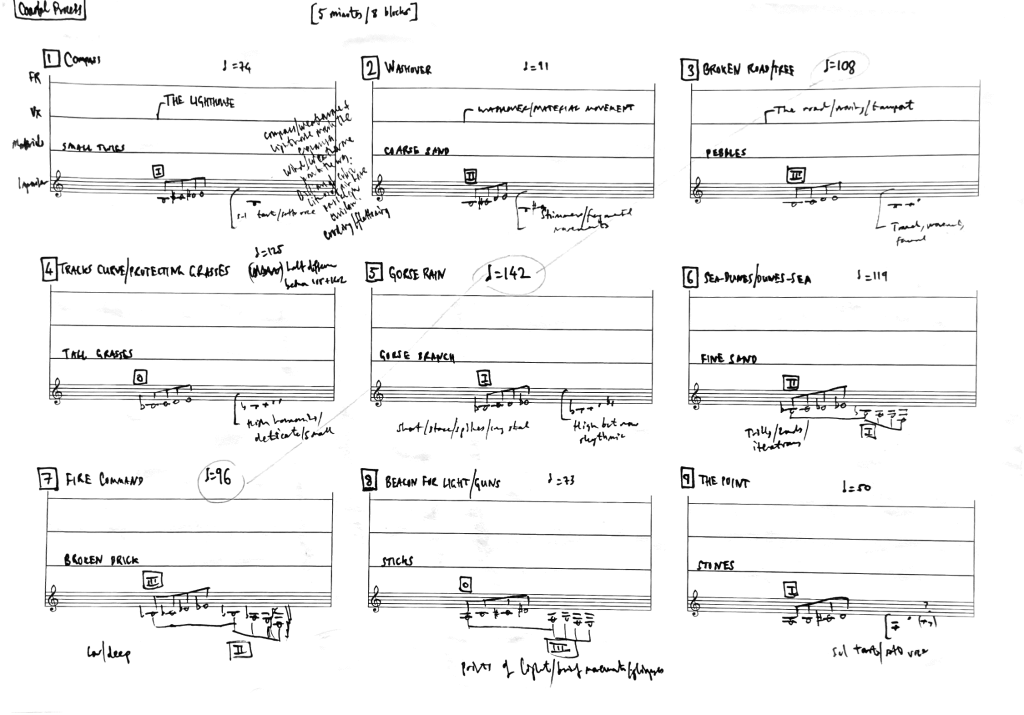

Here’s my sketch for the work as a whole, which plots out the 9 field-recording locations along with three other main elements: sonic layers, tempo structure, pitch material.

Sonic layers. The original plan was to have four layers of sound that could be used in various ways in the performance. 1) Field recordings (or FR on the sketch); 2) voices (from the interviews); 3) materials (such as the sounds of small twigs, sand of different coarseness, grasses, and stones – in other words, the stuff of Spurn); and 4) the improvising musician part.

As the work developed, the voice and material elements were dropped. Voices because the prospect of dissecting the interview recordings seemed out-of-step with the pressing need of the project to preserve participants’ voices – quite literally. To intervene and edit voices seemed an act of editorial destruction (who I am to say what words and messages should be heard and what shouldn’t?). Materials because that sense of materiality is so present in the field recordings (sand/water/grass/wildlife) that another layer either would get obscured in the sonic texture or might appear as a synthetic hallucination.

So, the final piece has three layers: 1) field recordings; 2) generative string parts (which I’ll talk about in another post); and 3) improvising musician(s).

Tempo structure. In quite a simple metaphor, there is a wave-like structure to the underlying tempo map spanning the 9 sections. Section 5 (the numerical central section) is the ‘fastest’ (at 142 beats per minute). The sections prior to this decay from 142 at 17BPM per section (giving 125, 108, 91 and 74 respectively). Though these tempi aren’t always heard in terms of rhythm, they determine the rate at which material turns over and imply a sense of build, of rushing towards the shore, up to that central section 5. After that through to the end of the piece, the tempo of each section deteriorates by 23 each time (giving 119,96, 73 and 50) giving a sense of a longer retreat, of slowing down or pulling further away from shore.

Pitch materials. The pitches that are suggested for improvising musicians to use are express as 4-note scalic clusters (known technically as tetrachords). This is a feature of the way I’ve determined pitch materials for quite a number of years before. In this piece, they lend themselves to a way of thinking about developing pitch material across the piece as analogous to single grains of sand moving southwards along the coast via processes of longshore drift. Each pitch is a grain of sand whose accumulations create the sum-total effect (a beach, a wash of sand). Each tetrachord ‘decays’ by one of its pitches dropping by one semitone each time (e.g. the D-sharp of the opening tetrachord becomes a D-natural in section 2). Over the course of the piece, these drifting descending semitones create tetrachords of different musical character (derived from tone-semitone intervallic structures) that, all being well, prompt different improvised musical responses. These clusters are physical as much as music theoretical.

So, that’s how the material of Coastal Process was formed. How I got from an 8-mile transect walk to a piece of music that is about and of that place.