What does Spurn Point sound like?

What does a 3-mile strip of land, jutting into the North Sea, sound like? How can we get a sense of how a large area sounds, when sound has a finite circumference – a bubble of invisible ripples in which we have to stand to be able to hear it?

The total sound of Spurn Point can never be grasped. It’s too long, too dispersed. So, I needed a plan for how to understand how Spurn sounds, but on a human scale. My intention for writing a piece of music in response to Spurn was always to make it of the place – not really about it as such.

This way of thinking has been a fundamental way I’ve worked for quite a few years now. Back in 2018, I started exploring the east coast of East Yorkshire through sound stretching from the dramatic cliffs of Flamborough Head’s North Landing to the concrete confidence of the Humber Bridge (which also took in the lighthouse on Spurn Point). On a day of coastal adventure in August 2018, I went to the cave on the North Landing beach (which is only accessible during lower tides) to explore its acoustics and soundscape. As a result, I wrote Elegy for a Resonant Space which is a piece providing a structure for improvisation for any portable instrument asking the musician to perform not just in and space but with it.

This is the relationship I want to have with places. And it’s the relationship I want to weave into the fabric of the music I make as a result.

Telegraph Poles & Transect Walks

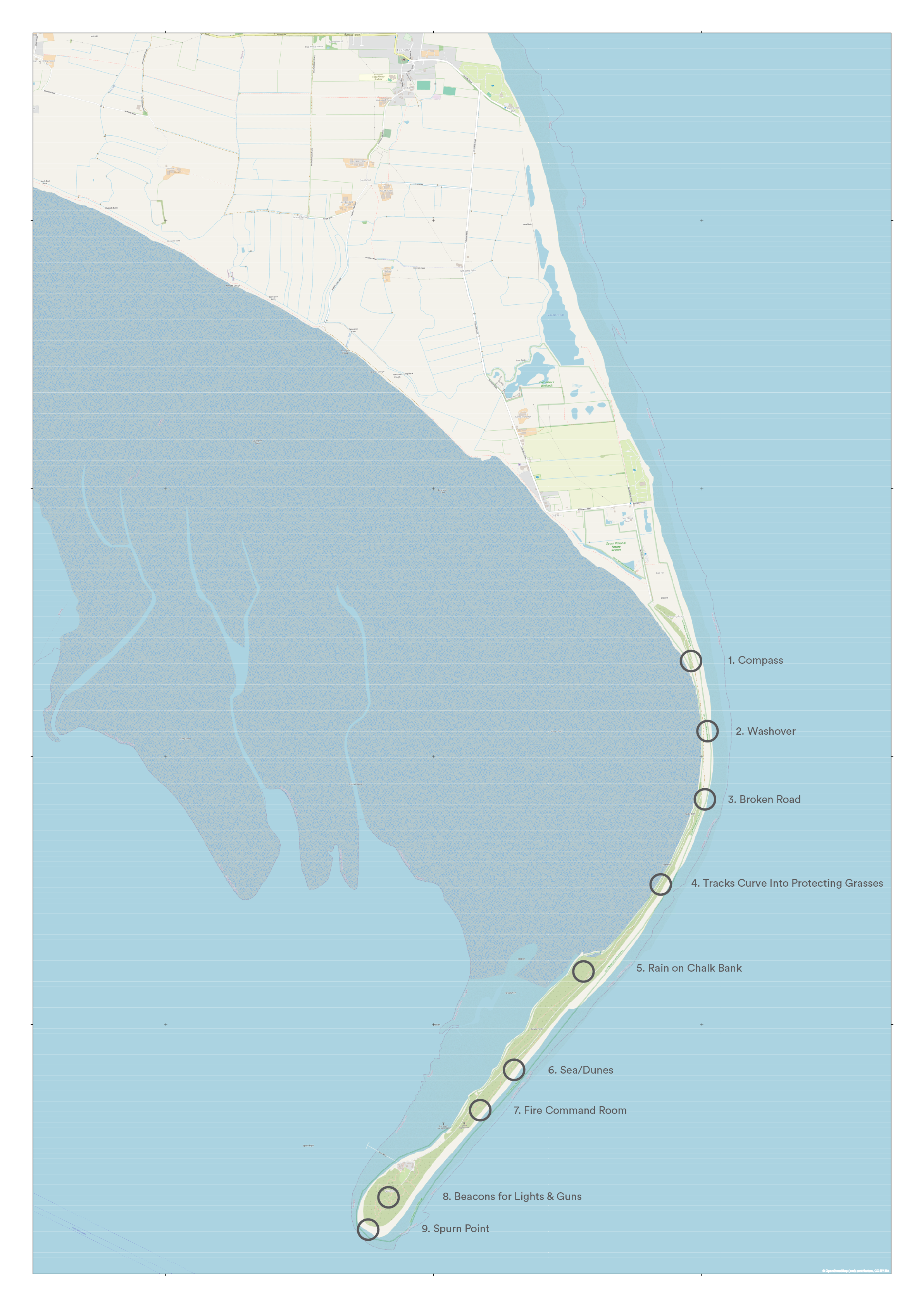

So, how to grasp Spurn’s sound? There were two influences that shaped what I eventually did. The first of these was the interview given by Andy Gibson in February 2022. In this interview, Andy talks about a long line of telegraph poles that stretch along the peninsula (until the flood of 2013 that washed them away). These telegraph poles were significant features of the landscape (cropping up on childrens’ drawings on school field trips). They were also numbered, and people would refer to a great spot for fishing at number 44 as a way of marking the land. This spine, used for orientation, inspired the plotting of my route in sound.

Second was an interview exploring Rob St John’s work exploring the Finnish island of Örö published by Anton Spice on his Through Sounds Substack in October 2023. Örö has a couple of similiarities with Spurn in that it has been a military site in the past and is a place of striking natural beauty. Spice invokes the idea of a ‘military-pastoral’ complex of ‘military ruins and resurgent biodiversity’, which someone visiting the southern parts of Spurn might recognise. St John recounts the challenges of the dark and the cold, and how to explore such a place through sound. He describes an approach that he borrows from biology and geography called a ‘transect walk’, which is essentially a way of parsing the landscape in some way to ‘sample it. St John says:

I’m interested in the way sound transitions across the landscape, the way it appears and disappears across scales of time and space. I’d draw these arbitrary lines and record every 100 steps…

I decided to try this ‘transect walk’ approach with Spurn Point, heading out there on Wednesday March 20th 2024 (a cool day, not much breeze, but with the ever-present threat of rain). My plan was to record for 5 minutes, walk for 10 minutes and record again. There can probably never be a perfect durational plan for something like this – something will always be missed, something favoured over something else. But as my first foray into doing a transect walk (having done different kinds of field recording before), I had to start somewhere.

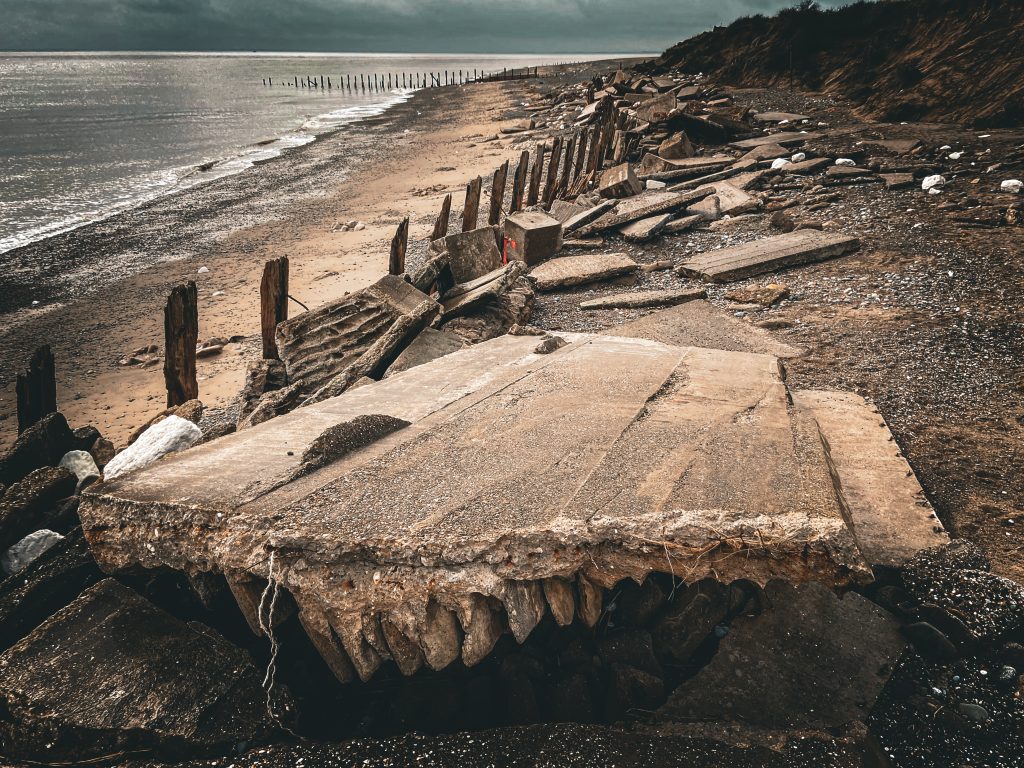

My thinking was that Spurn is, in parts, characterised by long tracts of land with similar traits. The washover is an example of this. I wanted to capture enough field recording audio to underpin a sizeable section of music and I wanted to capture a range of different landscapes down the spit. I also needed to know I could get to the end of the peninsula and back in less than about 6 hours, so it was also partly a decision about practicalities (there are tides to consider).

Instead of drawing an arbitrary line on a map, I decided to follow a route based on my intuitive flow across the landscape on the day. Sometimes that tracked existing pathways and bridleways. At other times, I ventured into less well-trodden areas. My approach is somewhere between a ‘line transect’ and a ‘point transect’. As it worked out, I recorded in nine locations and captured around 45 minutes of audio (which you can explore here along with the panoramic images I took in each place).

Map & Locations

The locations were given titles describing the place or reflecting what caught my attention at the time:

The walk totalled 8.75 miles (14km) so the technical set-up had to be portable and easy to use. For the technically minded, I used an SPC microphone (which enables 360-degree recording using its 84 capsules in 32-bit) and a fully charged MacBook Pro the SPC recording software. I could’ve taken a smaller rig, but making the recording in such a way kept all possibilities of spatial audio open for later and avoided the need for a separate interface or for fiddling around with levels. The only other piece of kit was a couple of plastic bags in case of rain (which were needed for the deluge that began just as the final recording was completed).

I am cautious about the word ‘capture’, which I’ve used several times. It describes the freezing of a moment or the taking of something to keep for yourself. Of prising something from its habit, or of refusing something its freedom. We use it all the time to describe the creation of recorded audio. Perhaps, in the case of sound, this is not so problematic as my ‘capturing’ of the sounds of Spurn doesn’t rob it (or anyone) of them. They just keep flowing in. But the risk perhaps lies in the idea that these recordings are the sounds of Spurn, instead of just one very brief moment in its post-glacial history.

The transect walk field recording trip was step one in the creation of the piece that eventually became Coastal Process. The nine-part structure, determined by the durational spacing of record-walk-record, became the nine-part scheme for the music. The sense of traversing a landscape tesselates with the focus on improvised musicianship. The imagined single piece of sand, moving and accumulating to create the landscape we see, becomes the metaphorical structure for treating pitch. More on this another time.

The sounds, then, are (as you might expect) of the sea. But of different kinds of sea interacting with different kinds of landscape (conquering feeble concrete roads in ‘Broken Road’, relentless churning in ‘Washover’, and gently coaxing in ‘Sea-Dunes’). The sounds are also of fleeting wildlife (a chorus of geese moving across the field of view in ‘Tracks Curve Into Protecting Grasses’ or skittery birds in ‘Gorse Rain on Chalk Bank’). There are human voices just at the start near Warren Cottage, but they don’t persist much further.

Past the washover, there’s a constant hum from the shipping crossing east-west on the horizon. A diesel-fuelled substrate to the exposed sounds of the ongoing coastal process.